The 5 Percent: Can we change the health trajectory of rising-risk patients?

According to the noble mission statements of academic medical centers, we are committed to “healing humankind,” “advancing human health,” “alleviating suffering,” and “improving the quality of life” of the community, the country and the world.

But here’s the thing: If we’re really responsible for looking after the health of individuals, then the scope of our work extends way beyond even the ambition of our tripartite mission of clinical care, research and education. It means caring for the health of our communities. And that is mind-blowingly complex.

What we’ve come to realize—and admittedly it has taken us a while—is that doctors alone cannot take this on. Health happens at the intersection of individuals, families, employers, pastors, teachers, philanthropists, politicians, a team of health care providers, and countless community workers and nonprofits. But the question remains: Who is responsible for making those critical connections? Who’s in charge? And who is going to pay for it? That’s not how we’ve organized ourselves. That’s not what we’ve trained for. And, most of the time, that’s not what we’re paid for.

“There’s so much headwind we have to confront here to be more conducive to truly doing population health,” says Matt Longjohn, M.D., MPH, the YMCA’s National Health Officer and Vice President for Community Integrated Health. “There wasn’t anyone at my medical school who told me what it would be like to work with the YMCA,” says Longjohn who graduated from Tulane University in 1999. The fact that Longjohn is the YMCA’s first physician-executive in its 165-year history is a sign of how community-based organizations are becoming important partners in transforming health. “We’re moving from being the interesting panel at the end of the conference to being part of conversations in board rooms,” he says. YMCA population health initiatives range from afterschool and healthy-eating programs, to diabetes prevention and arthritis management at thousands of sites across the country. For community organizations like the Y, that’s hopeful. “We have a role to play,” he says, “and people to help and savings to provide.”

Longjohn’s message to academic medical centers? Pick up the phone and call us. Partnering with organizations like the YMCA will mean that we transition from practicing on the population to practicing with the population. And those partnerships can be powerful. A trial of the Y’s Diabetes Prevention Program at Indiana University in 2004 formed the basis of research that led the CDC and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to adopt the protocol nationwide. Partnerships with the LIVESTRONG Foundation (a 12-week cancer survivorship program) to Harvard University (a healthy food and fitness model for afterschool programs) and others are making a difference.

Forging her own population health partnership, University of Utah Chief Wellness Officer Robin Marcus, Ph.D., picked up the phone and called car dealer Mark Miller. The goal was to help a population learn about and manage their health. By working with the University of Utah Health Plan, she was also hoping to help those with emerging chronic conditions who may be about to become intensive users of the health care system.

Forging her own population health partnership, University of Utah Chief Wellness Officer Robin Marcus, Ph.D., picked up the phone and called car dealer Mark Miller. The goal was to help a population learn about and manage their health. By working with the University of Utah Health Plan, she was also hoping to help those with emerging chronic conditions who may be about to become intensive users of the health care system.

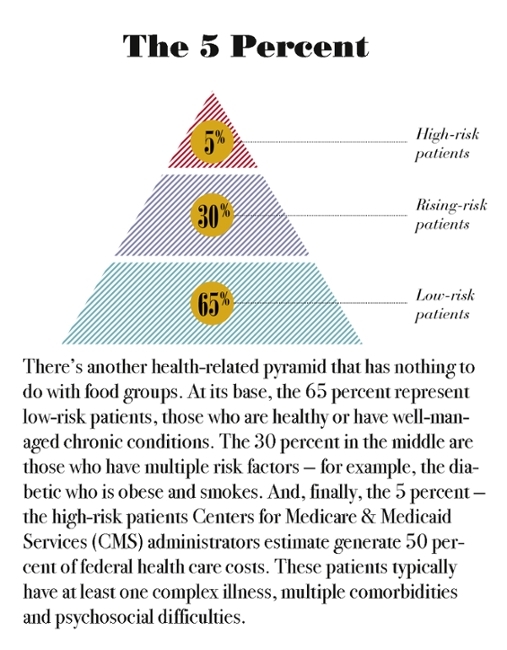

Population health initiatives usually focus on one issue at a time—childhood obesity, diabetes, hypertension—because tackling all of it all at once seems impossible. But many patients struggle to manage multiple challenges—cancer and diabetes and heart disease and depression. CMS administrators estimate that five percent of Medicaid patients generate 50 percent of its costs and increasingly are beginning to think of them as a unique population that needs more of our attention.

Marcus believes that we have not focused enough on this “all-of-the-above” crowd. Not only do we want to take better care of this population, says Marcus, we want to create interventions for those who are heading in that direction. Getting to those people before they become patients will require coordination between employers, insurers and health care experts, Marcus says. Whether it’s saving money, reducing lost work time, or improving health, there needs to be something in it for everyone.

With their public-private partnership, Marcus and Miller are piloting the health intervention at Miller’s Salt Lake City Toyota dealership. Miller is paying up-front to have a part-time wellness coach talk to his employees (and their adult partners) about nutrition and stress and exercise, and also track each individual’s medical history to see who is on the verge of becoming high risk. They are targeting specific wellness interventions to the people who can benefit the most, while still trying to engage everyone in their own health. When medical care is needed, it’s expedited by working closely with their health plan, keeping Miller’s workers out of the emergency room and on the showroom floor.

Marcus is first to admit that the literature on employer-based wellness programs, a $6 billion industry, has been underwhelming. “I hope we can show that wellness can’t just live in HR,” she says. “We need to engage employers and insurers and individuals in a meaningful way.” “If we really want to make a difference, we need to focus less on people who are already fit and more on helping people who just don’t know how to change their lives, or have mental health challenges, or financial barriers, or just bad luck,” Marcus says.

At the end of a year, she hopes that the dealership’s employees, especially at-risk patients, will be healthier and happier with their care, and Miller’s insurance premiums will go down.

But she has one more hope. If this pilot is successful, Marcus plans to use it as a model that can be replicated elsewhere. “We’re changing payment models in this country,” says Marcus. “And when the fee-for-service situation changes to bundled care, we’ll be able to demonstrate value.”

These kinds of partnerships may be the best way to make population health more than a buzzword or a theoretical concept or a source of frustration for providers, Longjohn says. And doctors are going to have to push, to become ever more vocal advocates for their sickest, most disenfranchised patients, he says. Longjohn reminds us that in the year 2000, the Association of Academic Medical Colleges contributed to a revised charter for the American Board of Internal Medicine, a sort of update to the Hippocratic Oath that acknowledged the care in a clinic or hospital room is not enough. Our patients live in a social and ecological nest that clinicians have to be aware of and respond to.

These kinds of partnerships may be the best way to make population health more than a buzzword or a theoretical concept or a source of frustration for providers, Longjohn says. And doctors are going to have to push, to become ever more vocal advocates for their sickest, most disenfranchised patients, he says. Longjohn reminds us that in the year 2000, the Association of Academic Medical Colleges contributed to a revised charter for the American Board of Internal Medicine, a sort of update to the Hippocratic Oath that acknowledged the care in a clinic or hospital room is not enough. Our patients live in a social and ecological nest that clinicians have to be aware of and respond to.

“The role of the clinician is to get out of just being at the bedside,” says Longjohn. “We can’t just live in ivory towers. We have a responsibility to speak out about inequities in health and act upon the potential to address them.”

Rebecca Walsh is a Senior Writer for University of Utah Health Sciences.